How much of the female disadvantage in late‐life cognition in India can be explained by education and gender inequality?

Written by: Urvashi Jain

Published on: May 26, 2022

India is among one of the most gender unequal countries, and this notion has been backed time and again based on gender lopsided indices like imbalanced sex ratios, low rates of female labor force participation, and women’s overall disadvantage in multiple dimensions of human capital like health and education. Much of what is known about gender inequality in India has focused on women at younger ages like childhood, adolescence, and reproductive ages. Relatively less is known about gender disparities at older ages. This has been partly due to lack of suitable datasets which focus on aging, and partly due to a larger proportion of young population. Demographic changes underway in India however project that the country will soon have to contend with population aging, as the proportion of those aged sixty and older is set to reach 19% of the total population by the year 2050. Hence, we need to know more and understand the unique challenges faced by this population, especially paying attention to questions at the intersection of aging and gender inequality.

In a recently published research article in the journal Scientific Reports, we used data from India’s first nationally representative aging study, the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), to examine the gender disparity in cognitive function among adults aged 45 and older. The paper was motivated by two broad and important questions. First, how much of the female disadvantage in later-life cognition can be explained by early-life factors like socioeconomic status, childhood nutrition, and education? In high income countries, where women’s educational attainment is equal to or higher than men’s on average, the gender gap in cognition at older ages is either non-existent or women have higher cognition test scores. In low- and middle-income countries the magnitude of the gender gap in cognition is lower among younger cohorts, which can be partly attributed to increasing levels of women’s education. However, this association between education and the gender gap in cognition needs to be examined with greater nuance, which led to our second motivating question for the paper – is education equally beneficial in reducing the female disparity in cognition across all contexts, or could it be that in environments with high levels of gender inequality, more education might not be enough to close the gender gap? In other words, are there any complementarities between individual-level educational attainment and the macro-level gender inequality, and how do these shape population level cognitive health in India?

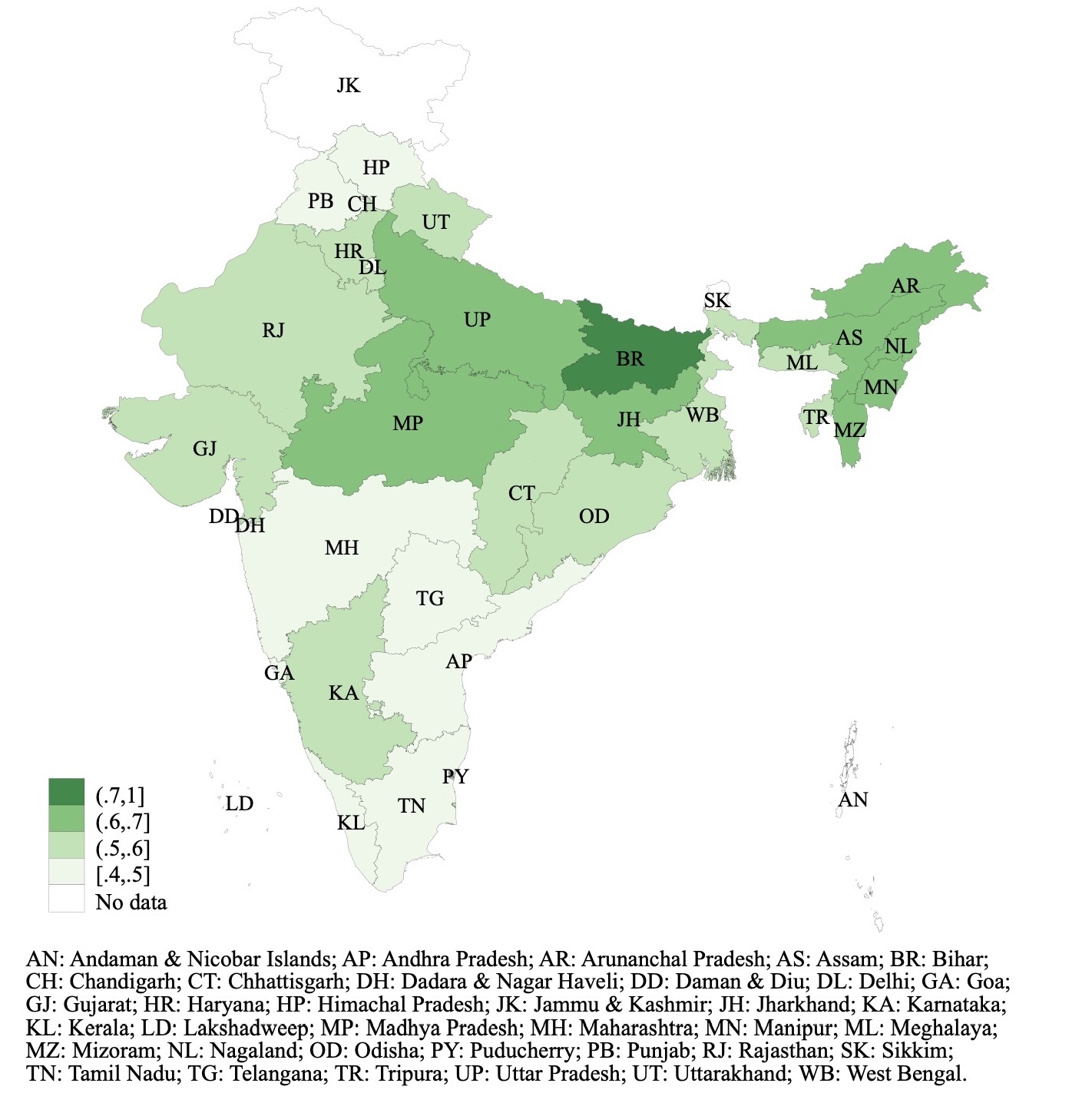

To capture macro-level gender inequality in India, we developed a state-level Gender Inequality Index (GII), following the United Nations Development Programme's (UNDP) definition. To get a sense of the sheer magnitude of gender inequality in India, let’s compare GII across Indian states (Figure 1), and with some other contexts. The Indian states of Himachal Pradesh and Kerala had the lowest values of GII (0.45), while the state of Bihar had the highest (GII of 0.73). Contrast this with a country like Sweden, which has far less gender inequality, with a GII of only 0.05.

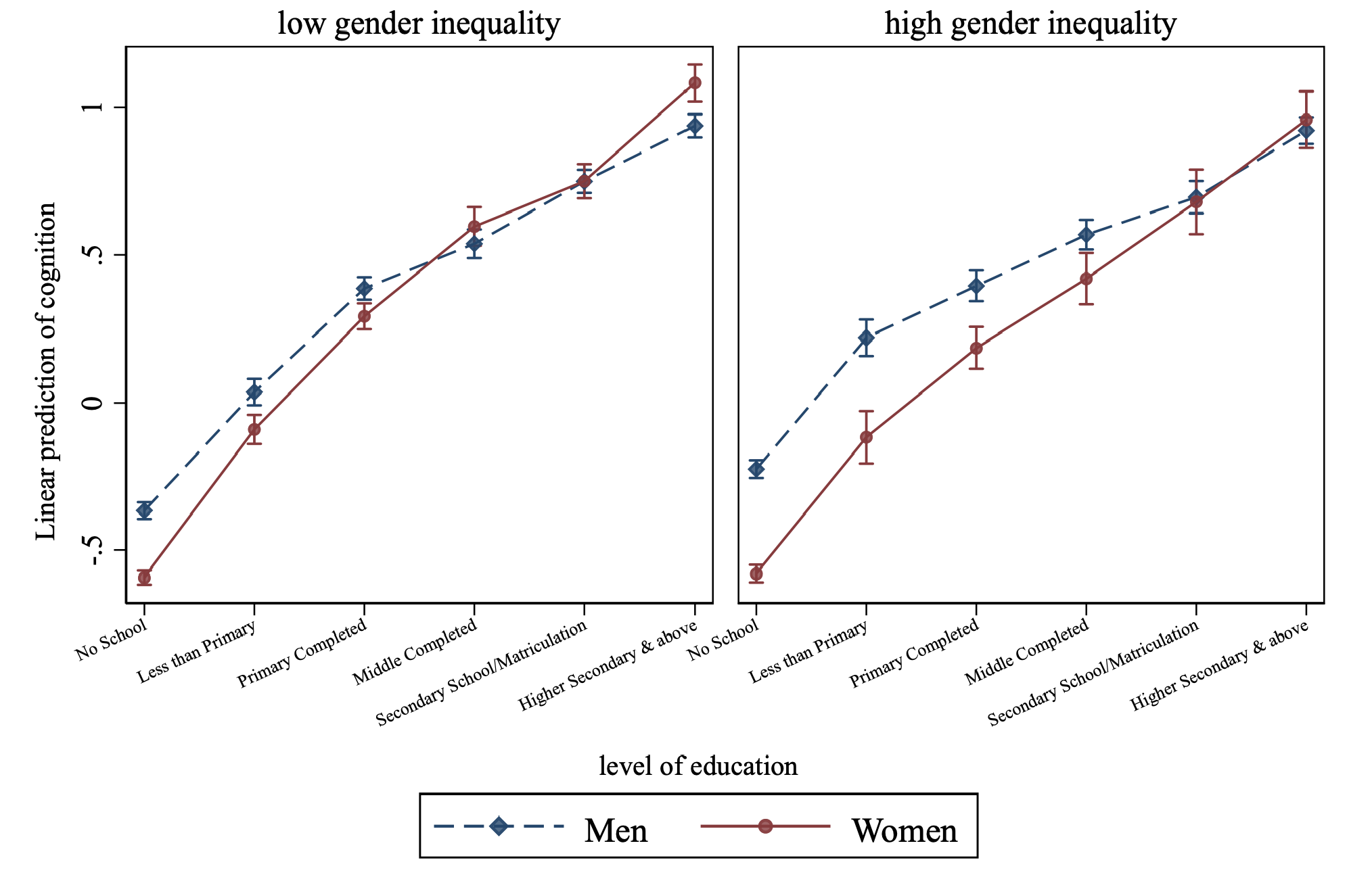

When we compared cognition of men and women, we find that the standardized cognition score was lower by approximately 0.6 standard deviation among women compared to men in our sample. The answer to the first question we posed was that early-life socioeconomic status, nutrition, and education explain up to 75% of the female disparity in late-life cognition in this large sample of older adults in India. This however also indicates that a quarter of this gap was unexplained by the models we used. To answer the second question about the nature of complementarity between individual-level education and macro-level gender inequality, we examined the differential association of education with later-life cognition by gender, and then further by gender and regions of high vs low gender inequality. We found that even though higher education was associated with better cognition for both genders, each progressively higher level of education was associated with a greater increase in cognition for women compared to men. Moreover, the rate at which education helped close the gap in cognition was faster in regions with relatively more gender equality (Figure 2). In states with high gender inequality, women needed a much higher level of education before their predicted cognition score was at par with men.

The findings strongly suggest that a) education is a key factor determining long-term cognition, but does not explain the gender differences entirely, and b) education and contextual gender inequality complement each other in shaping population level cognition. How might these findings be useful to policymakers in India? First, India has made great strides in closing the gender gap in educational attainment over the past decades, and while there’s still a long way to go in achieving complete gender inequality in this domain, educating women will continue to pay dividends in the long run as it helps improve women’s health, which directly translates to a lower disease burden. However, the older cohorts of women with low levels of schooling are a vulnerable sub-population due to lower levels of health, especially cognitive health, and ought to be paid special attention. As per the Dementia in India 2020 report, the number of dementia cases among Indians aged 60 and older is projected to reach 14 million by 2050. Identifying at-risk groups is bound to become a public health priority – gender and education level will play a key role here. Second, merely closing the gender gap in educational attainment is not enough. Gender inequality is multi-dimensional, and gains in one dimension cannot substitute for deficits in other dimensions. Our results clearly show that even after achieving similar levels of education, older women’s cognitive health is not at par with men’s if they are living in regions characterized by high gender inequality. Hence, we urge policymakers to pay attention to reduce to gender inequality along all dimensions, since it can affect long run health outcomes, casting a shadow as far as among the older populations.

- Urvashi Jain is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Mitchell College of Business, University of South Alabama.